The Book They Blamed

Anastasia Higginbotham had no idea that her book had caused such an uproar that it was blamed for legislation passed by the Texas legislature, thousands of miles away from her home base in New York.

She was even more surprised to find out that it had been read on the state senate floor in the middle of the night.

Higginbotham, who crafts her books by hand in collage using grocery bag paper and recycled materials, launched the series Ordinary Terrible Things in 2015 with a book called Divorce Is the Worst. Through the series of books designed to help adults and children discuss difficult subjects, she’s tackled topics including death, sex, and her most recent book – Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness.

It’s the latter, published in 2018 and the winner of the International Children’s Library White Raven Book award, that has some in an uproar.

Enough of an uproar that a resident accused Highland Park ISD of implementing it in its curriculum. Enough of an uproar that the claim was repeated several times throughout the debate on House Bill 3979.

(Read:Our coverage of the Texas legislature’s 87th session)

Higginbotham watched the video clips of the discussions on the state senate and house floors with equal parts bewilderment and bemusement.

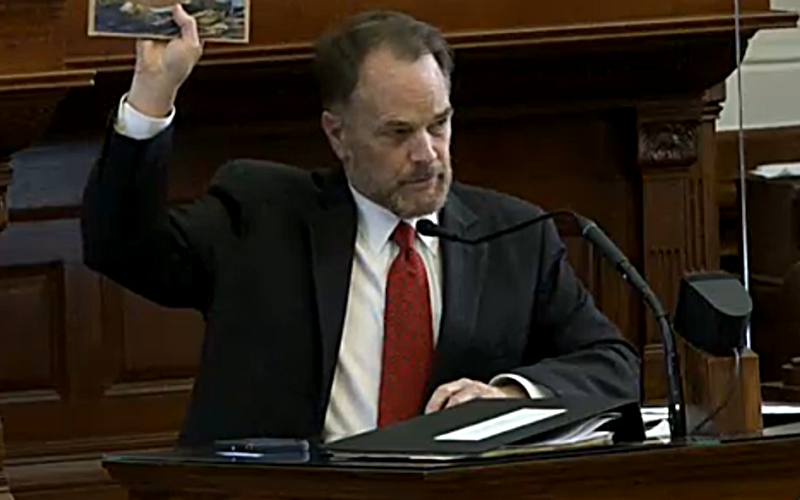

“Hey, they’re waving it around,” she said, chuckling ruefully. “This was my promotional campaign all along.”

Someone paid to have copies sent to all 150 members of the Texas house, according to a letter sent by the bill’s author, State Rep. Steve Toth. Depending on whether the members were provided hardback or paperback copies, that could mean the representative spent $1,500-$3,000 on a book he considers reprehensible. A request to Toth’s office asking for an accounting of the book purchase has not garnered a response.

In a letter to Texas House members, Toth claimed that “this book was recommended to students by teachers in Highland Park Independent School District near Dallas.”

At several points in an hours-long debate in the Senate, State Sen. Bryan Hughes referenced Highland Park ISD, claiming that the district was teaching from Higginbotham’s book. The district denied that claim and said the book wasn’t in the libraries at all.

Hughes and other lawmakers had frequently referred to HPISD and the book throughout the discussions around HB3979 and its companion bill, SB 2202, with nobody really challenging them on it.

Until, that is, that night, when two lawmakers challenged the assertion — first, on its factual basis, and second, on the contents of the book.

State Sen. Nathan Johnson (D-Dallas), whose district includes the Park Cities, took Hughes to task for his assertion that HPISD was teaching from this book, telling him that he checked, and it’s not on the curriculum, nor is it in any school library.

Hughes said that he was told by a parent that a teacher recommended the book.

“It’s one teacher, one kid, one book, and one district and one time at best — and we don’t even know if that’s true,” Johnson said. “If you’re wondering what’s going on in my district, that’s not it.”

State Sen. Borris Miles (D-Houston) took Hughes to task about the contents of the book, asking him if he had read it.

“I’ve read about 10 to 12 pages,” Hughes said. “The tabbed pages.”

Miles asked Hughes if he was aware that Higginbotham was a white woman.

“No, I didn’t know that,” Hughes said.

“The purpose of the book was to teach white children how to dismantle white supremacy,” Miles said, prior to reading passages from the book. “What she was doing with this book was putting it in White, well-heeled communities, so she could teach those children and the cycle could be broken.”

And it’s that assessment, Higginbotham said, that is at the core of her book’s premise.

“It’s strange because it’s, there’s so much distortion involved,” she said, adding that it seems like it was actually a few people that were upset by the book. “And at the same time it’s been established that the book is not officially being used in any curriculum or any classroom. So small minority of people are upset about something that actually isn’t happening.

“That’s puzzling and to me, it is very in character with how whiteness operates — distortion is how it works best,” she said. “It’s, it’s a funhouse mirror on the truth. The truth is that you have this book on your bookshelf, the truth is the teachers work around the kinds of restrictions all the time to make sure that children have information about the world as it is, and as it was.”

Higginbotham said that this boils down to how much lawmakers trust teachers and librarians, too.

“I trust the teachers, I trust the librarians, and I trust the parents who are aligned with racial justice and with disrupting systems of oppression in their communities and in their homes,” she said. “It sounds like there’s plenty of support for a book like Not My Idea and the ideas within it, but the ones who are not in favor of it are the loudest and the elected majority.”

Higginbotham also said that those who think the book is designed to make people feel bad about being White have missed the point.

“I love the way that Senator Miles tried to clarify that my goal is to engage affluent parents who are White and families who are White, who could join in the collective efforts to assure more racial justice in the world,” she said.

“My goal is not to change anybody’s mind. That’s one thing, the goal of this book is to appeal to people who are already curious and who are already interested in racial justice and being part of a legacy of fighting for racial justice, and that includes White people,” she said, adding that White people have always been a part of efforts for social justice, following Black leaders of the civil rights movements.

“I want White people to be aware that we have a place in this. And we have skin in the game because it’s a system that we don’t, and we never consented to carry white supremacy forward,” she added. “We never consented to uphold it. It was not our idea, and we don’t need to defend it, right? So we have a choice to make about how we want to relate to race and racism. And if we’re White and we don’t want to be part of White supremacy, then we can make choices every day that are in line with that. My end goal is to get to as many white children as possible to let them know the game is rigged, and if you do not want to play by those rules, you do have a choice to make history the way you want it to be made. You, you get to study your own history and find out that there is a legacy of anti-racist movement and why people have been part of it. And you can take pride in that.”

Higginbotham said that one page of the book explained it best.

“There was a page, but so important in the book where I say, ‘You can be White without signing onto whiteness,'” she said. “And this is a place where people get really confused. And I understand that the confusion is part of learning about it, but skin color is not what makes you for or against racism – it’s your choices every day. And every person with every kind of skin color can make a choice to be anti-racist in every direction at every intersection of race and gender and ethnicity and culture and religion.”

Higginbotham said that the discussion over her book — and over critical race theory — underscores the fact that White people just don’t know how to talk about race with each other, let alone their children – but that it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t.

“You know, your kids ask you a question, you don’t know the answer – ‘Let’s look it up together,'” she said. “Your kids asked you a question and you think, ‘Wait, that’s not how I learned it.’ You could check it out yourself. Just be curious.”